Creating a New Class of Materials

Simple to produce. Hard to break. Yet stretchable and over 50% liquid. Those are a few of the qualities of a completely new class of materials created by Professor Michael Dickey and his colleagues.

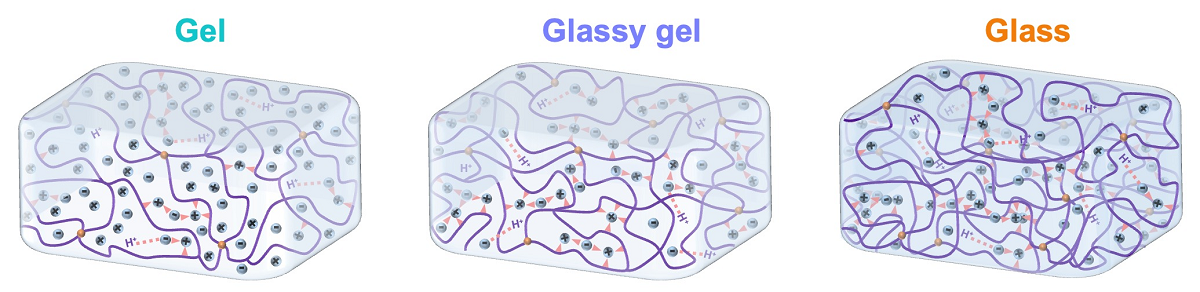

They’re calling the materials “glassy gels.” Essentially, glassy gels represent a combination of two classes of materials — gels and glassy polymers — that have historically been considered distinct from one another.

“We’ve created a class of materials that we’ve termed glassy gels, which are as hard as glassy polymers but — if you apply enough force — can stretch up to five times their original length, rather than breaking,” says Professor Dickey, corresponding author of a paper on the work and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at NC State.

Stiff and brittle, glassy polymers are used to make things like water bottles or airplane windows. Gels, on the other hand, contain liquid and are soft and stretchy, making them great for products like contact lenses.

Glassy gels are effectively a material that combines some of the most attractive properties of both glassy polymers and gels. To make glassy gels, the researchers start with the liquid precursors of glassy polymers and mix them with an ionic liquid. This combined liquid is poured into a mold and exposed to ultraviolet light, which “cures” the material. The mold is then removed, leaving behind the glassy gel.

“The ionic liquid is a solvent, like water, but is made entirely of ions,” says Dickey. “Normally when you add a solvent to a polymer, the solvent pushes apart the polymer chains, making the polymer soft and stretchable. That’s why a wet contact lens is pliable, and a dry contact lens isn’t. In glassy gels, the solvent pushes the molecular chains in the polymer apart, which allows it to be stretchable like a gel. However, the ions in the solvent are strongly attracted to the polymer, which prevents the polymer chains from moving. The inability of chains to move is what makes it glassy. The end result is that the material is hard due to the attractive forces, but is still capable of stretching due to the extra spacing.”

Glassy gels bring the best of both worlds — simultaneously exhibiting some of glassy polymers and gels’ most attractive properties.

What’s more, Dickey and his research team have also shown glassy gels possess properties that could make them an effective alternative to certain commonly used plastics.

“Considering the number of unique properties they possess, we’re optimistic that these materials will be useful,” says Meixiang Wang, co-lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral researcher with the Dickey research group.

For example, Wang says glassy gels can conduct electricity more efficiently than comparable plastics commonly used today.

“A key thing that distinguishes glassy gels is that they are more than 50% liquid, which makes them more efficient conductors of electricity than common plastics that have comparable physical characteristics,” Wang says.

Another reason the researchers believe glassy gels look promising for various practical applications is they’re easy to make.

“Creating glassy gels is a simple process that can be done by curing it in any type of mold or by 3D printing it,” Dickey says. “Most plastics with similar mechanical properties require manufacturers to create polymer as a feedstock and then transport that polymer to another facility where the polymer is melted and formed into the end product.”

Watch this video made by members of the Dickey research group to learn more about glassy gels and their physical properties.

Dickey and Wang published their findings in Nature this past summer. UNC-Chapel Hill’s Xun Xiao, with Wang, was a co-lead author of the paper.

Titled “Glassy Gels Toughened by Solvent,” the paper’s co-authors include Salma Siddika, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at NC State; Mohammad (Milad) Shamsi, a Ph.D. graduate from the Dickey research group; Ethan Frey, a former undergraduate student in the Dickey group; Brendan O’Connor, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at NC State; Wubin Bai, a professor of applied physical sciences at UNC-Chapel Hill; and Wen Qian, a research associate professor of mechanical and materials engineering at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“We’re excited to see how glassy gels can be used and are open to working with collaborators on identifying applications for these materials,” Dickey says.

This article is based on a news release from NC State University.